How I Wrote a Memoir: Part IX

The missing workshop feedback, what I found in my parents’ garage, and my first true writing advisor.

Remember at the beginning of this series when I said I saved everything related to my writing for the last fifteen years? I lied. The only drawback of an in-person workshop is when the feedback is handwritten on hardcopy pages, the stack gets large, and when you move as often as I have, and you eventually publish the essay you revised in that 2013 UCLA Extension personal essay class—the “dead ex-student essay” from blog #8—you feed the pages into the shredder because you don’t think you need them anymore.

My Garage Stash

I hunted for the notes from my UCLA instructor and classmates in that ten-year-old workshop in my parents’ garage in the dusty plastic tubs with my childhood memorabilia, photo albums, and cases of CDs—yes, I saved those. Here’s what I found instead: two sets of small Sculpey clay hands and feet molded onto gnarled wire hangers my grandmother used to build unique, standing sculptures of Santa Claus at Christmastime. My cousin and I retrieved the creepy extremities—the last remnants of Granny’s unfinished art—hanging in “the cold room” in my grandparents’ empty house after the four-day estate sale before the house sold. They were the only items that didn’t sell. It’s no shock why.

Granny’s Unfinished Art

In my parents’ garage, I also found a stack of yellowing papers from the 1990s when I worked on my teaching credential at CSULB, where I wrote bad fiction about the same boyfriends who now appear in my memoir manuscript and one-page, single-spaced essays. The professor who assigned the “one-pagers” was a ruthless grader. Receiving a ten out of ten on one of his papers was next to impossible, and I did it more than once—total bragging rights! (Do you know hard it is to write an entire academic paper on one page? That’s where I learned to edit!) I didn’t think of him as a “mentor” because he was grouchy, arrogant, and uppity about who deserved the title of “professor.” (He did.) Students either loved him or hated him. I loved him, but he didn’t change my life.

An Accepted Essay That Was Never Published

I didn’t find the helpful feedback from my UCLA Extension workshop cohorts in the garage, but I found the essay I wrote about my instructor—and now close friend—on my laptop. It was accepted for publication in 2014 but was never published. (R.I.P. Literary Mothers.) So, with a few minor edits, I am posting that essay here since it never made it to its intended online destination.

The piece is an homage to mentors, the compassionate, miraculous people who lift you up when you don’t believe your writing is up to snuff; whose words encourage you to keep going; who are the reason you decide, “Yes, I can write a book”; who—when you’re nearly forty years old and walk into class with a heavy backpack and a heavy heart—accept your first essay for publication in an anthology; invite you on a California book tour to promote the anthology; summon you to at-home workshops, where you write most of the essays that become the first draft of your manuscript; and tell the backstage bouncer at a punk show you’re an “official photographer” so he’ll let you into the Descendents’ trailer to babysit Milo’s kids while she interviews the band. These are the people who change your life.

It’s been said often before because it’s true: Writers must find their people. I hope you find your version of Shawna Kenney.

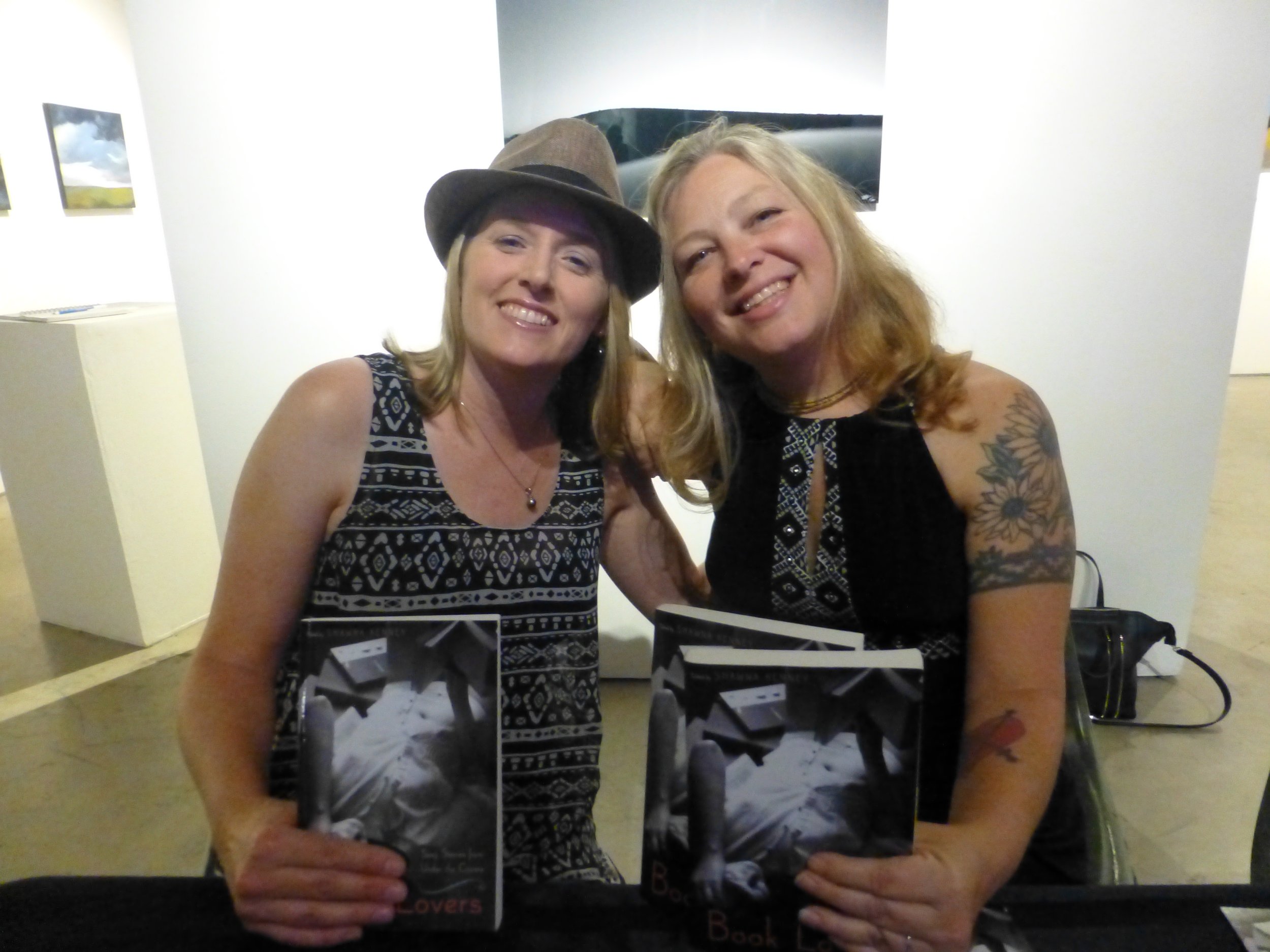

Center for Sex and Culture, San Francisco

Before getting to the meat of “how I wrote a memoir” in blog #10—when I actually start writing a book—here’s what I wrote about Shawna nine years ago:

“My Superstar”

March 2014

My 2013 New Year’s resolution was to start writing again. I was almost forty. I’d taken a number of online classes before, but I hadn’t written a word in two years. My latest workshop had deflated me. There I felt judged on my character more than my work. I was labeled based on one essay about one incident. The responses drove me into hiding.

I’m not good enough. This is as far as I’m going to get, I thought.

But when I’m not writing, I suffer.

So, after a two-year ego-healing break, I decided to try again. This time I wouldn’t hide behind the internet. I wanted face-to-face interaction with other writers.

I found Shawna Kenney’s UCLA Extension Writing the Personal Essay course on the university’s website. When I read her bio, I thought, “She’s my people.” It wasn’t the success of her memoir I Was a Teenage Dominatrix or the “award-winning” accolade in her title; nor was it the numerous literary publishing credits that reeled me in. It was the way she presented her approach to teaching. I knew she would be positive, practical, and nurturing.

I wasn’t wrong. In her ten-week class, I handed out the same essay that incited the negativity that caused me to quit writing in the first place. I wasn’t giving up on it. It’s a story of forbidden sex, desperation, and death. It is not a flattering portrait of me, but it’s true and doesn’t represent all that I am. I knew it was a story I needed to tell.

Dispersing twenty hardcopies, I was terrified. My hands shook. But Shawna had already created a safe space for her students to be themselves and put forth their best work without judgment. I had hope.

At this point, I didn’t call myself a “writer,” only “someone who writes—sometimes.” My first in-person workshop changed that. Shawna and my fellow writing students spent an hour discussing the merits of my work, providing constructive observations that would help me make the piece better. After that, I was eager to submit more material.

I anticipated Shawna’s feedback. She wrote, “You have such a natural writing voice,” and, “You make yourself vulnerable on the page.” She called my first workshop essay “a post-modern romantic tragedy.” Words like “publish this!” and “I could see something like this in The Believer” sustained me.

She asked the right questions: “What does this narrator want more than anything?” and she never questioned my ability to succeed in the future: “I look forward to reading another adventure in dating written in this voice!”

It’s Not Dead Fest 2015, San Bernadino

After previous writing classes, I’d have the best intentions; then I’d stop writing when I wasn’t held accountable because of a debilitating fear of failure. I’m still afraid, but I move through the fear as a result of the bravery I see in Shawna.

In 2013 and beyond, I continued to “ride the Shawna train,” I joked, and took two more of her ten-week workshops, as well as an online writing prompt class. In fall 2013 I submitted an essay to Shawna for a Seal Press anthology she was editing: Book Lovers. She accepted it. I never would have written the essay if she hadn’t asked me, “Are you going to submit something for my book?” It was a particularly difficult essay to write and the first one I published in print.

Because of Shawna’s insight and guidance, I learned to call myself a writer without wincing. I tell strangers I meet, “I’m writing an essay collection,” because I am. It’s an arduous task I always thought unattainable; now I have 105,000 new words because she gave me the freedom to write them.

She also arranged for public readings. I’ve now read in public six times, three times to promote my story in her anthology. I was afraid for people to read my work before I met her. Now I love to hear people’s reactions live when I’m in front of a microphone. I have a newfound confidence I couldn’t have imagined.

As a writer pre-Shawna, I was paralyzed by perfectionism. My editing background made it impossible for me to get words on a page, always worried about the finished product. I now follow her example and know I can fix the words as long as there are words to fix.

I’m “doing the work,” she says. “It’s just a draft,” she tells us.

Her carefree attitude is matched by her intelligence and her own ability to craft. “There’s a reason she’s the teacher,” one of my classmate’s said after reading Shawna’s anthology introduction.

Shawna published a piece in xoJane’s “Unpopular Opinion,” an essay she called very unpopular on Twitter. Of the hundreds of comments posted under the piece, many were downright cruel. Instead of discouraging me from publishing, this only gave me more resolve.

I’ll never please everyone, I thought. If Shawna can have the courage to take this verbal backlash, so can I.

She calls us her “supah stahhhhs” and her “lovelies.” At the end of a long weekend in San Francisco, after two terrific readings and Q&As, we hugged on the street and cried, and she said I was “the female Davy Rothbart.” I’ll take it.

I know now that if I don’t ever publish the book I’ve been writing in my head for forty-one years—the same one that’s now forming on paper—it will be because I choose not to, not because I can’t. Because of Shawna, I’m tackling my passion with “all [my] Chelsey vigor.” She’s my superstar, my editor, and friend. Today I thank her on the page.

Northern California Book Lovers Tour